By Amina Ojelabi

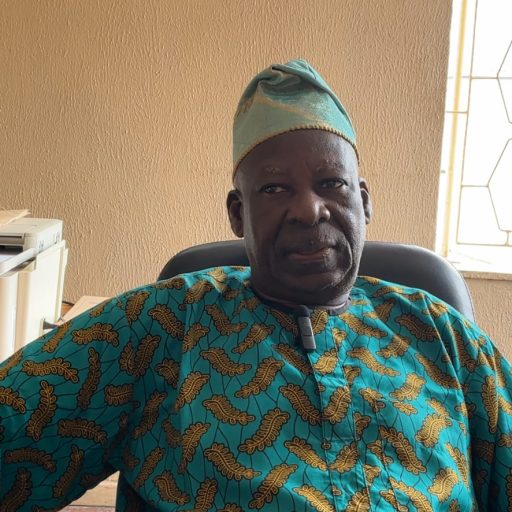

Captain Adewale Ishola is a seasoned master mariner and former President of the Nigerian Association of Master Mariners. In this interview, he speaks on critical issues affecting Nigeria’s maritime, to the erosion dangers of dredging, aging port infrastructure, and the urgent need to revive the national shipping line.

Let’s talk about sand mining and dredging. What impact do they have on the environment and navigation?

Dredging has both positives and negatives. On one hand, it deepens waterways, allowing vessels to move freely without grounding. On the other hand, it causes coastal erosion, making shoreline communities vulnerable to flooding. As we dig out sand, water flows further inland, impacting villages that never used to experience such water levels. So, while navigation improves, there’s an environmental trade-off.

Dredging is often promoted as a development strategy. But you’ve spoken about its environmental downside. Can you explain?

Yes, dredging helps deepen channels for easier vessel movement that’s the positive side. But the downside is that it often causes erosion along the coast. As we remove sand, we change water flow patterns, and water starts moving into places where it didn’t before. This leads to flooding in shoreline communities that are unprepared for it. So while dredging improves navigation, it can seriously endanger coastal settlements if not managed properly.

What’s the difference between capital and maintenance dredging?

Capital dredging involves creating or significantly deepening a new waterway or channel. Maintenance dredging, on the other hand, is about sustaining existing depth levels that have already been dredged. Lagos Channel Management, through an MoU with the Nigerian Ports Authority, carries out maintenance dredging on Lagos waters. It’s a continuous process especially in areas with heavy siltation.

You mentioned that many of our ports are outdated. What’s the current challenge with ports like Apapa and Tin Can Island?

These are old ports. Apapa was built during the colonial era, and Tin Can was developed in 1975 because of congestion at Apapa. They both have limited depth at the quayside, which restricts the size of vessels they can accommodate. As a result, larger vessels conduct ship-to-ship transfers offshore because they can’t berth inside. This isn’t efficient for a modern economy.

What about Lekki Deep Seaport? Does it address this limitation?

Yes, Lekki is a game changer. It’s designed for deep-draft vessels that our older ports can’t handle. It’s the direction Nigeria must go building more deep seaports like Badagry to attract global shipping lines and reduce pressure on Apapa and Tin Can.

Some ports like Warri and Calabar remain underutilized. Why is that?

The main issue is siltation. These ports lie along sandy bottoms. Even after dredging, the sand flows right back in. So no matter how much you dredge, the problem returns. That limits the safe draft to around 6.5 meters, which restricts the size of vessels. Lagos and Port Harcourt are luckier they don’t have this problem, so bigger vessels can go in and out more easily.

Let’s talk about water safety. What are your concerns?

Safety has two aspects personnel and vessel safety. Are the crew trained? Do they have valid STCW certifications? Are vessels seaworthy and properly maintained? Are environmental guidelines being followed? If a vessel goes aground, it becomes a wreck and poses hazards to others. Safety also means ensuring personal protective equipment is worn and that operations follow standard procedures. One mistake at sea can be catastrophic.

You’re a vocal advocate for reviving the national fleet. Why is that so important?

Because Nigeria is bleeding without it. We had over 24 vessels under the Nigerian National Shipping Line (NNSL). We trained our own cadets, built our own maritime workforce. Since it was scrapped in 1995, we’ve depended entirely on foreign vessels to export crude and import goods. We’re losing millions of dollars daily.

What’s the best way to bring the fleet back? Government-owned ships again?

Not necessarily. I believe in a public-private model. NLNGNigeria Liquified Natural Gas runs a similar system where the government owns 49% of the fleet and private investors own 51%. Nigeria can adopt this. Let government provide the seed support through CVFF or bank-backed loans but let professionals manage it. Politics must stay out of it. Look at Dangote’s refinery; it worked because it was driven by professionals with clear structure and commitment. That’s what the maritime sector needs too.

Final thoughts?

The maritime sector is Nigeria’s hidden goldmine. But we need discipline, investment, and structure to unlock it. Reviving the national fleet isn’t just about ships it’s about training, job creation, trade dominance, and economic sovereignty. We did it before. We can do it again.

Leave a Reply